Fidan Mirhanoğlu on how hopes of oil led delegates at Lausanne to ignore Kurdish claims to self-determination.

Fidan is a researcher at the Institut Français de Géopolitique.

In Kurdish when someone deliberately ignores something, they say that the person in question is “turning a deaf ear like Ismet.” The saying remains common in Kurdish villages a century after Lausanne. Ismet’s selective deafness at the conference allegedly explains the failure to establish a sovereign Kurdistan. But were the Kurds genuinely forgotten at Lausanne, or did the Powers deliberately overlook them in pursuit of their own interests? As French archival documents show, members of the French and British delegations corresponded about the Kurds and negotiated over them with Ismet (Inönü), the chief Turkish delegate.

In a telegram of May 3, 1923, one member of the French delegation reacts to a statement from Sir Horace Rumbold announcing that the British would be evacuating Mesopotamia. “It seems hard to believe that the British government has made such an important determination without receiving certain guarantees from the Turkish side…One is tempted to ask oneself if Ismet Pasha’s sudden decision on February 4th to concede on all the issues of the treaty concerning England…and the policy of intimidation and hostility towards us, inaugurated on the same date, have not been the result of a promise made by Lord Curzon.” [1] If we wind the clock back to 1919, however, we find a British official, F. R. Maunsell, writing of the Kurds in a very different vein:

In considering the question of self-determination for the races of Eastern Turkey in Asia it becomes necessary to study the history and characteristics of the Kurd & Armenian races who have inhabited the Northern & more mountainous part of the country since the dawn of history. More especially is this necessary in the case of the Kurds whose role in history is frequently overlooked and their presence as a distinct race with rights for self-determination as valid as the Arab & the Armenian, is often ignored entirely. Alas it is of the utmost importance from the point of view of British interests to determine from the characteristics and moral value of the various races whether it is possible to utilize them to create a solid block of friendly peoples from the Persian Gulf to the Black Sea to thwart the Pan Turanian movement of the Turks which if left unchecked would certainly spread Eastward & in time threaten the safety of our Indian Empire.[2]

F. R. Maunsell

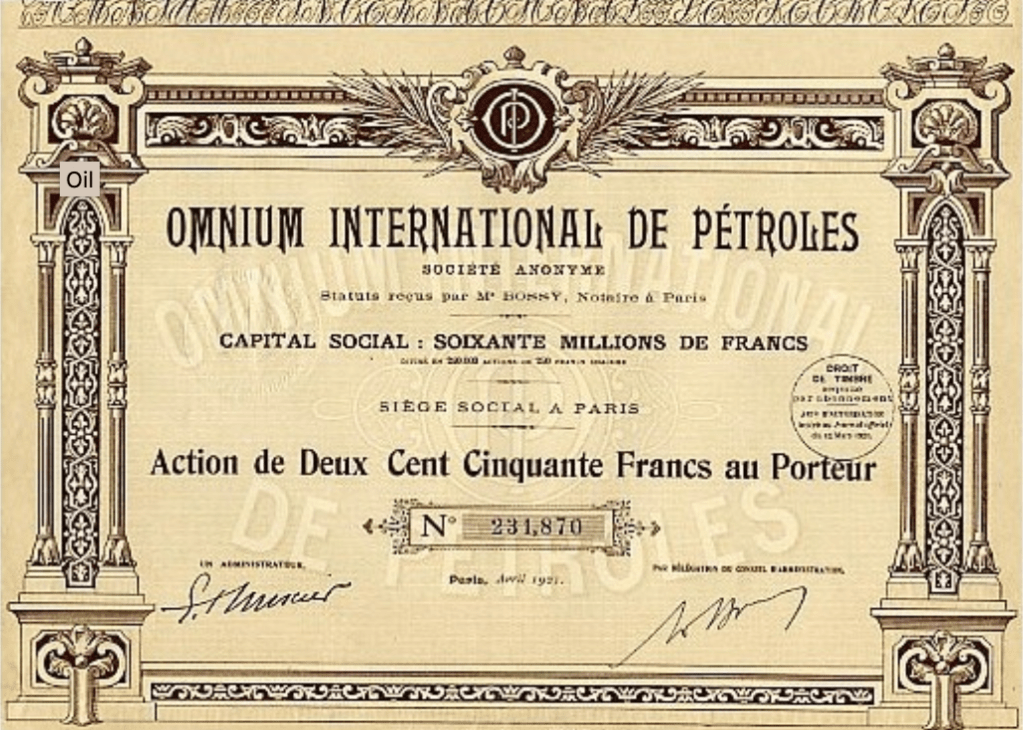

One of the motivating factors behind this shift in British position towards the Kurds was the oil wealth of the territories they inhabited. The French also took an interest in Kurdistan’s oil, as shown by a 1921 letter of introduction presented to French delegate General Maurice Pellé by a M. de Boulard, an official from Omnium International de Pétroles. Presided over since 1920 by Ernest Mercier, who would later play a leading role in the early history of the Compagnie Française des Pétroles (the oil major known today as TotalEnergies), Omnium had been founded in 1911. Its main oil production lay in Romania, but in the early 1920s it was actively searching for new fields, including in the Caucasus. [3] It was not strictly speaking French, with significant participations by the Waterkeyn group (Belgian), Royal Dutch-Shell (Anglo-Dutch), and even Standard Oil (America). All were content to keep a low profile and exploit Omnium’s “French” identity: the more Omnium could “appear as an independent French group”, the easier they could exploit the French foreign ministry’s support in their own interests.[4]

In the aforementioned letter the company is described as “a French company with a capital of 60,000,000 Francs”, formed “with the strong encouragement of General Gouraud.” The name-dropping of a military leader – Henri Gouraud was commander of the French Army of the Levant – is characteristic of oil negotiations in the period, which saw many veteran commanders of Allied forces transformed into lobbyists for oil companies eager to avail themselves of their contacts. The letter goes on to explain that Boulard’s mission was to establish contact with the Turkish Government to secure concessions “particularly in Kurdistan, where, according to our information, there are surface indications that suggest the presence of significant oil resources at depth.”[5] As Zeynep Oguz noted in a TLP podcast, the false assumption that surface indications of oil (such as oil seeps) constitute proof of “significant oil resources” persists to this day among the Kurdish population of southeastern Anatolia, fuelling conspiracy theories surrounding the Lausanne Treaty’s fictional “secret clauses”.

Another French report of May 24, 1923 notes that “two battalions of the West Yorkshire and Cameronian regiments, previously sent to the Mosul region, have returned to Baghdad”, and that “Sheikh Mahmoud has been authorized, upon his request, to present himself to the British authorities in Baghdad.” Sheikh Mahmoud, of the Barzanji clan of Sulaymaniyah in present-day Iraqi Kurdistan, had led a series of revolts against British forces in the region in 1919 and in 1922, when he declared himself the King of Kurdistan. As far as the French were concerned, his trip to Baghdad as well as the pulling back of the British regiments were indications of a “secret agreement” between the British and the Turks, under which “Mosul vilayet and a part of Kurdistan would be ceded by the British.”[6].

Curzon’s failure to get Ismet to back down over Turkish claims to the Mosul vilayet at Lausanne had made him unpopular in London.[7] At the Foreign Office Undersecretary of State Sir Eyre Crowe sought to negotiate with the Turkish delegation behind Curzon’s back, and the Turkish delegation was invited to send two representatives to London. But Prime Minister Andrew Bonar Law insisted there should be no such back-jobbing in London likely to undermine negotiations in Lausanne.[8] Downing Street, the Foreign Office, the Board of Trade and Colonial Office were working at cross purposes, culminating with a showdown between Curzon and Walter Long in late January 1923 [9] If the secret Anglo-Turkish agreement on Kurdistan mentioned by the French actually existed, therefore, there was little hope of it being implemented in a coordinated fashion, and, of course, Mosul vilayet remained within the British mandate of Iraq.

The Treaty of Lausanne had a profound impact on the Kurdish struggle for independence. A century on, oil is once again on the agenda in the region of Iraqi Kurdistan. The Paris International Trade Association recently determined that the Kurds do not have the right to negotiate their own oil agreements, despite the fact that the Iraqi Kurdistan Region has signed such agreements with international oil companies in the past, independent of Baghdad. The Paris decision nonetheless led the Region’s authorities to promise to coordinate future oil concessions with Baghdad. [10] A few days later TotalEnergies signed a major oil and gas project in the Iraqi capital. [11] That same day, representatives from Turkey visited Iraqi Kurdistan and held meeting to discuss oil and natural gas. History seems to be repeating itself, a century on.

Fidan Mirhanoglu’s scholarly publications include a recent article in Studies in Ethnicity and Nationalism entitled “Oil or State? The Role of the Oil in the Recognition of Kurdish Statehood in Iraqi Kurdistan”.

Notes

[1] Archives de la Ministère des Affaires Étrangères, 116 PO/EN 131 – 24 IV.

[2] The National Archives, WO106/64.

[3] See François Pelletier, D’Une Guerre A l’Autre: l’Itineraire Petrolier d’Ernest Mercier (Brussels: Peter Lang, 2020); Gregory P. Nowell, Mercantile States and the World Oil Cartel, 1900-39 (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1994), pp. 173-4. For Omnium’s foundation and early history, see Archives Paribas, Combs La Ville-Quincy, 473/19 and Archives Groupe Total, La Défense, 92.1/1 and /2.

[4] Calouste Gulbenkian to Henry Deterding, 4 Sep. 1920. Shell Archives, The Hague. 195/175c.

[5] AMAE 116 PO/EN 131 – 38VIII.

[6] AMAE 116 PO/EN 131 – 24 IV.

[7] R. Lindsay to Curzon, 5 Dec. 1922. Parliamentary Archives, BL/G/13/18.

[8] Bonar Law to Curzon, December 1922. Parliamentary Archives, BL/111/12/42.

[9] United Kingdom Parliamentary Archives, BL/111/12/57 and /61.

[10] https://www.20minutes.fr/monde/4036961-20230515-irak-attend-accord-final-turquie-exporter-petrole-kurde [11] https://www.lefigaro.fr/societes/totalenergies-et-l-irak-signent-un-contrat-de-10-milliards-de-dollars-pour-un-megaprojet-202307104.

FEATURE IMAGE: APERÇU GENERAL DE LA DIVISION ADMINISTRATIVE DES PROVINCES ASIATIQUES DE L’EMPIRE OTTOMAN, ARRANGÉ APPROXIMATIVEMENT PAR H. KIEPERT (DETAIL).

One thought on “Deaf Sentence”

Comments are closed.